Can I Wear the Global War on Terrorism Ribbon

All our charts on Terrorism

What is terrorism?

In our overview of terrorism, nosotros try to understand how the number of terrorist acts varies around the earth and how it has changed over time. To do this, nosotros need a clear and consistent definition of what terrorism is, and how information technology's unlike from any other form of violence. This is non straightforward.

Terrorism is defined in the Oxford Dictionary every bit "the unlawful utilize of violence and intimidation, peculiarly against civilians, in the pursuit of political aims." We apace see that this definition is unspecific and subjective.1 The issue of subjectivity in this example means that in that location is no internationally recognised legal definition of terrorism. Despite considerable discussion, the formation of a comprehensive convention confronting international terrorism past the United Nations has always been impeded by the lack of consensus on a definition.2

The primal problem is that terrorism is difficult to distinguish from other forms of political violence and violent crime, such equally land-based armed conflict, non-state conflict, one-sided violence, hate crime, and homicide. The lines betwixt these different forms of violence are ofttimes blurry. Hither, we have a expect at standard criteria of what constitutes terrorism, as well as how it might be distinguished from other forms of violence.

The criteria for terrorism

Violent actions are usually categorised co-ordinate to the perpetrator, the victim, the method, and the purpose.iii Different definitions emphasise different characteristics, depending on the priorities of the agency involved.

In our coverage of terrorism, we rely strongly on data from the Global Terrorism Database (GTD), which defines terrorism as "acts of violence by not-country actors, perpetrated against civilian populations, intended to crusade fear, in order to achieve a political objective."four,5 Its definition excludes violence initiated by governments (state terrorism) and open combat between opposing armed forces, even if they're not-state actors. In our definitions section nosotros provide the GTD's more detailed definition, in addition to others such as that of the United Nations.

A few cardinal distinguishing factors are common to most definitions of terrorism, with minor variations. The following criteria are adapted from the definition given past Bruce Hoffman in Within Terrorism.half dozen

To be considered an act of terrorism, an action must exist trigger-happy, or threaten violence. As such, political dissent, activism, and nonviolent resistance do not constitute terrorism. In that location are, however, many instances around the earth of authorities restricting individuals' freedom of expression nether the pretext of counter-terrorism measures. Man rights groups, such equally Immunity International and Human being Rights Scout, publish reports on such cases of censorship.

The inclusion of damage to private and public property in the definition of terrorism is a indicate of contention, only it is generally accepted in legal and statistical contexts.

An action must also be carried out for political, economic, religious, or social purposes to count equally terrorism. For example, the terrorist system Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) has conspicuously stated its political goal to establish itself as a caliphate. Likewise, attacks perpetrated by white extremists take discernable sociopolitical motivations, and and so are considered acts of terrorism. Past contrast, violent acts committed without a political, economic, religious or social goal are not classified every bit terrorism, merely instead as 'violent crimes'

To be classified as terrorism, actions must be designed to take far-reaching psychological repercussions beyond the immediate victim or target. In other words, an action must aim to create terror through "its shocking brutality, lack of discrimination, dramatic or symbolic quality and disregard of the rules of warfare".vii

Additionally, targetting civilian, neutral, or randomly chosen people – generally, people not engaged in hostilities – is a necessary but not sufficient condition to institute terrorism. The United states of america Country Department includes in the definition of 'civilian', "armed forces personnel who at the time of the incident are unarmed and/or not on duty." They "also consider as acts of terrorism attacks on armed services installations or on armed armed services personnel when a country of military hostilities does not exist at the site."8 As such, actions during open gainsay, where a state of military hostility exists, do non constitute terrorism.

Terrorist actions must be also conducted either by an organization with an identifiable concatenation of command or conspiratorial cell structure (whose members vesture no uniform or identifying insignia), or by individuals or a small-scale collection of individuals straight influenced by the logical aims or example of some existent terrorist move and its leaders (typically referred to as a 'alone wolf' attack).

Finally, the activeness must be perpetrated by a subnational group or non-country entity. Equivalent actions perpetrated by the armed services of nation states are given dissimilar classifications, such as 'war crime' or one-sided violence.

Distinguishing terrorism from other forms of violence

Based on the criteria above, we can begin to separate terrorism from other types of violence based on some very simplified distinctions:

- killings perpetrated by non-state actors against civilians, which are not ideological in nature i.e. not motivated by a particular political, economical or social goal, are classified every bit homicide;

- violence perpetrated by non-state actors against civilians, specifically based on ethnicity, sexuality, gender, or inability, without political or social intent to cause widespread fright, is classified as a hate crime;

- violence involving open gainsay between opposing military machine is classified every bit country-based armed conflict, if at least 1 of the parties is the authorities of a state;

- if, in the scenario above, none of the parties is the regime of a state, this is classified as a not-state conflict;

- violence perpetrated past governments against civilians is classified as one-sided violence.9

How terrorism and other forms of violence overlap

But even with these distinctions in mind, there is not e'er a clear-cut purlieus between terrorism and other forms of conflict like civil war and violence targeting civilians.

The GTD codebook notes this: "there is often definitional overlap between terrorism and other forms of offense and political violence, such equally insurgency, hate crime, and organized crime". Given the difficulty of excluding such cases in a systematic mode, this database includes them wherever they meet the basic criteria that form the definition of terrorism. However, it also flags upwardly instances where the coders had doubts whether the effect would exist better characterised by i of these 'culling designations'. You tin explore this by downloading the total GTD dataset at their website. As such, there is a partial overlap between common definitions of terrorism and certain other types of conflict.

Another mode in which conflict researchers distinguish between different types of trigger-happy acts is in terms of the number of victims. The Uppsalla Conflict Information Plan (UCDP), for instance, only includes events involving at to the lowest degree 25 deaths – a requirement not present in GTD. Therefore many, just not all, of the events recorded in GTD will also exist counted in the UCDP data, which are the basis of our charts of non-land and one-sided violence.

As an example, the September xi attacks on the World Merchandise Center in New York City are included as both a terrorist attack in the GTD, and an episode of one-sided violence in the UCDP data, considering the perpetrators were members of the organised group Al-Qaida, and information technology resulted in more than 25 deaths. All the same, the Norway attacks on 22 July 2011, in which a right-wing extremist killed or injured more than 100 people, is included in GTD as a terror attack, but is not present in UCDP information, since the attacker was acting independently, and did not represent the government of a state.

We are therefore aware that at that place can be overlap between the data nosotros nowadays on terrorism and that which we present on disharmonize. This fact is a crucial bespeak in agreement the definition of terrorism and what the term means to people. Many of the terrorist attacks that have place today are events which many people would think of every bit a different class of violence or disharmonize. In fact, most terrorism really happens in countries of high internal conflict, because ultimately terrorism is another form of disharmonize.

How many people are killed by terrorists worldwide?

In 2017, an estimated 26,445 people died from terrorism globally.

Over the previous decade the average number of annual deaths was 21,000. However, there tin be significant year-to-year variability. Over this decade the global decease toll ranged from its lowest of vii,827 in 2010 to the highest year of 44,490 in 2014.

Terrorism oftentimes dominates media coverage. We are informed about attacks as shortly every bit they happen and many attacks claim the headlines. Whilst our attention is drawn to these events – just as the terrorists intend – such intense coverage can go far difficult to contextualize the true extent of terrorism. This is because the availability heuristic: our perceptions are heavily influenced by the most recent examples of information technology. We're biased to recent events in the news because we can recall them quickly.

How many people die from terrorism relative to other causes?

In this chart nosotros run across global terrorism deaths in the context of deaths from all causes. The size of the big rectangle corresponds to the number of deaths in 2017. The share of deaths from terrorism are shown in ruby. A very small fraction.

Shut to 56 million people died in 2017; merely over 26,000 of them from terrorism.10 Every 2000th decease – 0.05% – were from terrorism.11

But terrorist activity can vary a lot from year-to-year. Possibly 2022 was a specially low or loftier year. When we expect at the tendency – also shown in chart grade – over the past few decades we see it hovered from 0.01% to 0.02% over the 1990s and early 2000s; increased to 0.08% in 2014; before falling to 0.05% in 2017. It was therefore a relatively high year for terrorist deaths, but not the peak.

Global distribution of terrorism

Globally, over 26,000 people died in terrorist attacks in 2017. Where in the world did terrorists kill most people?

Which regions experience the nearly terrorism?

In this nautical chart we run into the number of deaths from terrorism by region in 2017. Of the 26,445 global deaths from terrorism included in the Global Terrorism Database, 95% occurred in the Middle East, Africa or South Asia. Less than 2% of deaths were in Europe, the Americas and Oceania combined.

This is also true when we await at the number of incidents, rather than the number of deaths. Every bit nosotros will run across in the following section, not only is there a strong regional focus but this is also heavily concentrated in only a few countries inside these regions.

Most victims of terrorism dice in the Middle East, Africa and South Asia. This hasn't always been the case. Guerrilla movements in Central and S America, for example, dominated terrorism in the 1980s.

Global map of deaths from terrorism

Terrorism is often regionally-focused. Merely within these regions it'south also concentrated inside specific countries. The Eye East and North Africa had by far the largest number of deaths in 2017; but not all countries were affected.

Nosotros see the number of terrorism deaths by country in this map.12 Republic of iraq – the country with the most fatalities in 2022 – accounted for 60% of deaths in the Middle East & North Africa. This was one-in-four terrorism deaths globally. Combined, Republic of iraq and Syria accounted for virtually 80% in the region, and one-in-three globally.

The same is true for Southern asia and Sub-Saharan Africa which also had high death tolls in 2017. In Southern asia, most deaths occurred in Transitional islamic state of afghanistan, with high numbers in Pakistan and Bharat too. But some countries in the region – such as Nepal – had almost none.

Looking at the where in the world terrorism happens highlights an important indicate: information technology tends to be in countries with high levels of internal disharmonize. Here we hash out in detail the challenges of separating terrorism from other forms of conflict such as civil war or homicide. This proves difficult because often there is a stiff overlap.

If we look at a recent list of terrorist incidents across the world – have June 2022 every bit an instance – we see the bulk are events that most people would empathize to be terrorism: roadside bombings; machine detonations; attacks on religious or political institutions. Although usually performed by one or a modest grouping of individuals, almost are affiliated with well-known terrorist groups, such equally Islamic State, Taliban, Boko Haram, and Al-Shabaab. Again, most people would conspicuously associate these with terrorism violence.

But where the lines become blurred is that many of these groups are insubordinate or insurgency groups in various domestic conflicts. Islamic State, for example, is a primal instigator in the Syrian ceremonious war; Al-Shabaab in internal Somalian conflict.

This ways that nearly terrorism occurs in countries of high conflict because the internal conflict is – to a certain extent – terrorism.

The map below which shows terrorism as a share of full deaths for each country. In virtually countries – particularly across Europe, the Americas and Oceania – deaths from terrorism accounted for less than 0.01%. They are rare in well-nigh countries of the world today.

This is non true everywhere. In a number of countries across the Centre Eastward and Africa, terrorist deaths reach upwardly to several per centum. Iraq was the near affected iv.3% of all deaths were due to terrorism in 2017, followed by Transitional islamic state of afghanistan, Syrian arab republic and Somalia which each had over 1%. These are countries where overall conflict – of which terrorist activity is a part – is high. In fact, as we discuss here, the boundary betwixt terrorism, conflict, one-sided violence or civil war is non e'er clear-cut.

This map shows an overview for 2017. The extent of terrorism in nearly countries is very low. But – as we mentioned in the global-level data – this can change from year to yr [you can see this on the map higher up using the timeline on the bottom of the chart]. Attacks can be non-existent for many years before an unexpected rise or fasten. What effect does this have?

The United States provides an important case. Terrorism deaths in most years are very few: typically below 0.01% of all deaths. This unexpectedly spiked with the 9/xi attacks – the globe'south nearly fatal terrorist result of recent times. It claimed 3000 lives, accounting for 0.12% of all deaths in the US in 2001. Every 800th decease in the U.s.a. in 2001 was from nine/11. Nosotros should therefore exist enlightened of this volatility: having few deaths from terrorism in one year is non a predictor for the next.

Overall we see that terrorism deaths globally – and in most parts of the globe – are relatively rare. Much more common risks – oft ones that we can influence – impale many more people. An estimated 7 million deaths each year result from smoking; four.7 meg from obesity; and 3 meg from outdoor air pollution. The say-so of terrorism in the daily news cycle can mean that we lose perspective of this.

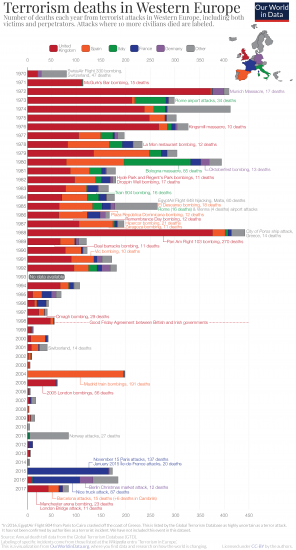

Has terrorism increased in Western Europe?

When things get increasingly visible in the media, it's easy to presume that they're becoming more common – psychologists refer to this phenomenon equally the availability heuristic.13 It tin can be difficult to separate a rise in attention from a rising in frequency. Increasing attention on terrorism can therefore make it seem similar it's ever getting worse. But is this really true?

Has terrorism in Western Europe been increasing?

In this visualization we shown terrorism deaths in Western Europe since 1970. Here nosotros use data from the virtually comprehensive database to date: the Global Terrorism Database (GTD). Another useful resources which cross-references well with this database for Western Europe is the Wikipedia entry: yous tin can find farther context of item events at that place.

The 1970s and 1980s were dominated by 'The Troubles' in Northern Ireland. Here nosotros run across annual deaths from terrorism in the social club of hundreds, and reaching over 400 deaths in some years. The U.k. was home to the largest share of deaths for much of the 70s, 80s, and 90s.

We come across quite a marked decline post-1998 with the Good Friday Understanding betwixt British and Irish governments. Since the Millennium the annual expiry toll has been below fifty deaths in almost years, and oft beneath ten. For context, compare that to how many people die on the roads: in 2022 effectually seventy people died every day in road incidents.14 Road accidents kill more people in Western Europe every day than terrorism in an boilerplate yr.

The year to year changes are however volatile. Big terrorist attacks – such as the Madrid train bombings in 2004; 2005 London bombings; 2011 Norway attacks; 2022 Paris attacks; the truck attacks in Squeamish and the Berlin Christmas market assail in 2015; and the Manchester and Barcelona attacks in 2022 – take occurred since the turn of the century.

This trend is also reflected when nosotros look at the number of terrorist attacks.

With exception of the 1970s, terrorism data in Western Europe can be hard to see when bundled with other regions. This in itself is an important point: terrorist deaths in Western Europe are very low within the global context.

During the 1970s Western Europe was abode to the most terrorist deaths globally: in many years 70% to 80% of recorded deaths from terrorism. This has changed dramatically since then. In 2017, only 0.3% of terrorism deaths occurred in the region.xv

Betwixt 2000 and 2022 – over almost ii decades – in that location were just nether 1000 deaths in Western Europe from terrorism. This is equal to the expiry toll of just ii to three years during the 1970s.

Has terrorism increased in the United states?

The Global Terrorism Database (GTD) – the nearly comprehensive database of terrorist incidents to date – was founded and is currently maintained from programmes in the United states of america. This, combined with the fact that terrorist incidents would take been covered extensively in the US media dating back to the 1970s makes information technology likely that it has the near complete record of terrorist attacks in recent decades.

In this visualization nosotros show the almanac decease cost from terrorism in the US since 1970. The September 11 attacks in New York stand out as the nigh fatal terrorist event in the globe in recent history. In fact, claiming the lives of about 3000 people, the death toll in 2001 was almost four times higher than the combined deaths from terrorism in the Us since 1970.

Based on fatalities nosotros run into terrorism was relatively high in the 1970s, then comparably 'quiet' – with exception of major outlying years, 1995 and 2001 – in the decades which followed. Over the last v years there has been a minor but steady increase in terrorist deaths in the United states of america.

In most years terror attacks caused fewer than 50 deaths per year, and in many years no one died from attacks. With exception of 2001, terrorism accounted for less than 0.01% of all deaths in the Usa in every year since 1970. For comparison, around 120 people die in road accidents in the United States every day.xvi This means the annual decease cost from terrorism in near years is equivalent to one-half a day or less on the country's roads.

When we await at the number of terrorist attacks we come across a marked turn down since the early 1970s.

Airline hijackings

- How often are airlines hijacked?

How often are airlines hijacked?

Airline hijackings are a very visible course of terrorism. The 9/eleven attacks in New York were the most prominent instance. But whilst hijackings tin seem like a mod grade of terrorism, they have a long history: in fact, hijackings today are very rare and much less frequent than the by.

Airline hijacking – sometimes termed 'skyjacking' – is the unlawful seizure of an shipping, either by an individual or an organized group. Most commonly, hijackers would demand the pilot wing to a specific location, or sometimes hijackers would attempt to wing the aircraft themselves.

Incidents of hijacking have been around most as long equally man flying itself with suspected hijacks dating equally far back equally 1919, and the first recorded hijacking in 1931. But they were still relatively rare until the 1950s.

In this chart nosotros see the annual number of hijacking incidents and fatalities globally from 1942 onwards. This data is sourced from the Aviation Rubber Network, which provides up-to-appointment and complete information on airliner accidents across the world. Hither we see very few incidents in the 1940s, with a minor ascent through the 1950s and 1960s. Until 1968, there were never more than ten incidents in a year.

But from 1968 to 1972, there was a sharp rise in hijackings – particularly in the Us. This is often chosen the "Gilded Age of hijacking" where hijackers would frequently need to be taken to a specific location (often Cuba) or demand big amounts of money as ransom. Over this v-twelvemonth period there were 305 hijackings globally. Most ended in no fatalities: 46 were killed, 25 of which happened in 1972.

The "Golden Historic period" was brought to an end in 1973 when the Federal Aviation Assistants (FAA) in the US introduced rules which required the screening of all passengers and carry-on luggage before boarding passenger aircraft. This is a measure nosotros accept for granted today.

Over the period from 1973 until 2001, hijacking incidents across the world were fairly consistent, in the range of effectually 20 to 40 per twelvemonth. In most years at that place were very few fatalities, although these were interspersed with fatal events which would impale tens of passengers.

2001 is the major outlier. Despite at that place being a relatively minor number of events – just xi, which was low by historic standard – the events of ix/11 made it the well-nigh fatal. 4 airliners were hijacked, two of which were flown into the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center. two,996 people died as a result of the 9/11 attacks, making it the most fatal terrorist incident in recorded history.

Regulation was speedily tightened. This resulted in a sudden decline in hijacking following the 9/xi attacks, with very few incidents and near no fatalities. Cockpit doors on many aircraft are now impenetrable and reinforced; security checks are now standard in most countries, including domestic flights (at the time, many countries had no or random checks for domestic travel); and levels of airdrome screening have been tightened significantly.

They've been successful. Fatalities from hijackings are at present very rare.

The gamble of hijacking in perspective

Many people are worried most flight because of the perceived run a risk of terrorism. Some may avoid flying completely.

But it's important to put the risk of hijacking (and flying in general) in perspective. Aviation, especially commercial air travel, is very safe. If we put information technology in perspective of the number of the number of people flight, in 2022 there were just 0.01 deaths per million passengers: that's one death per 100 million. This has improved significantly since the 1970s when there was around 5 deaths per meg passengers.

Hijacking deaths are then only a very small fraction of the total from aviation. In this nautical chart we see the annual deaths from commercial airliners, and the number specifically from hijackings. This again highlights that hijacking fatalities are rare: with increased safety measures post-2001 there have been nigh none.

Half of Americans are worried well-nigh being a victim of terrorism

Spreading widespread fright is a key aim of terrorism.

How effective have terrorists been in this regard? How many of the states are really worried about terrorism?

Half of the US population are worried near about being a victim of terrorism

Many of the most comprehensive surveys on public opinion on terrorism accept been conducted in the United states of america.

This visualization shows public concern for terrorism in the US since 1995. The data, from Gallup Polls, here shows the share of respondents who said they were "worried" (the sum of those who said they were 'very' or 'somewhat worried') and those who said they were "very worried" about them or a family member becoming the victim of terrorism.17

Overall, around one-half said they were worried, of which around 10-twenty% were "very worried" of becoming a victim of terrorism. Throughout this period – with the exception of 2001 – less than 0.01% of deaths in the U.s. resulted from terrorist attacks. The average over the period from 1996 to 2022 was 0.006%.

We besides meet that concerns were spiking after large terrorist attacks in the US or European countries.18 There was an firsthand spike following the 9/11 attacks in New York and the 2005 London bombings; and a rise after the Boston Marathon bombings, and succession of attacks in Paris. When we see a recent attack in the news, we become more worried it will as well happen to us or family members.

We should treat these results with some caution. Information technology's not entirely clear what someone means when they ask the question: "How worried are yous that yous or someone in your family volition go a victim of terrorism?". Is this request near how likely we think this scenario is? The level of risk? Or simply whether nosotros'd be worried if there was a chance it could happen to us? People may interpret it differently. Many people might recollect the probability of this happening is low, but upon consideration they'd be worried that a family fellow member could be a victim.

Because of this we should study how people change their behaviors based on this fright. Here we find more evidence that many people in the US are worried almost terrorism.

More than a third in the US say they're less willing to practice sure activities because of terrorism

There are sure locations and activities that are often the target of terrorist attacks: busy public spaces or countries effectually the globe where attacks are more frequent.19 Especially in the US in the backwash of 9/xi, aeroplanes and skyscrapers will also be seen every bit a potential target for terrorism, even if the evidence suggests that plane hijackings are now incredibly rare.

The same survey as that referenced above besides asked respondents if they were or weren't less willing to practice sure activities after terrorist events in contempo years.

The chart shows the share of respondents who said they were less willing to practise such activities. Here we come across that a large share was willing to change their behaviors: over twoscore% said they were less willing to travel abroad; around a third were less likely to wing and go to crowded events; and one-quarter to go into skyscrapers.

Do we run across these claims when we look at actual patterns of behaviour?

A range of studies take looked at the impact of major terrorist incidents on airline demand, travel and tourism. Following 9/11 there was an immediate reduction in U.s. airline demand – given equally the number of passengers – of over 30%.twenty This big autumn did not persist at that level, but in the months and few years which followed, in that location was an ongoing reduction in need of 7.4%. Although passenger demand later increased over again, analyses suggest that domestic air travel did not return to the levels which would have been projected in the absence of the attacks.21 This was as well true of tourism to the United States in the years which followed 9/11.22

These studies didn't look at the distribution of reduced travel demand – whether information technology was people who stopped flight completely or just less often – so we tin can't directly tie information technology together with the Gallup survey results. But both seem to report the same finding: 9/11 had a negative impact on the willingness of people in the The states to wing.23

Which countries are most worried about terrorism?

In a divide mail service we looked at levels of business near terrorism in the The states. What most the residual of the world? Is it just as worried about terrorism?

To meliorate understand the global motion picture we can describe upon information from the Earth Values Survey (WVS). The WVS is a global enquiry project running for decades, which assesses public stance on a wide range of values and beliefs. For a range of questions it provides comparable data from across the earth.

In its surveys from 2010 to 2014, information technology asked the question: "To what degree are you worried about the following? A terrorist attack." Unfortunately not all countries were included in this detail question in the surveys. Simply the data is complete enough to provide perspectives across the world regions.

In the map we see the share of respondents who said they worry "very much" or "a great deal" about a terrorist assail. Similar to the results we presented above, 52% of U.s.a. respondents said they were worried. But, compared to other countries this was relatively depression. In some countries nigh everyone said they were worried: Rwanda, Tunisia, Georgia, Malaysia and Haiti had over 90%. Across many countries in the Middle East, Southeast Asia, Africa and Latin America more than 8-in-ten said they were worried.

Some countries scored much lower: Argentine republic with 26%; New Zealand and Sweden with 22%; and the lowest was the netherlands with only 10%.

What becomes clear here is that there is non a clear human relationship between business organization near and prevalence of terrorism. We see this in the scatter nautical chart which plots the share who are worried about terrorism in a given country, against its share of deaths which event from terrorism. In well-nigh countries the probability of being in a terrorist assault is very low: terrorism accounts for less than 0.i% of deaths each year – in many it is less than 0.01%. But even so, concern tin can range from x% to over 90% of the population.

In virtually countries levels of business organization are disproportionate to the likelihood of being a victim.

- Why exercise some terrorist attacks receive more media attention than others?

- Terrorism is over-represented relative to its share of deaths in media coverage

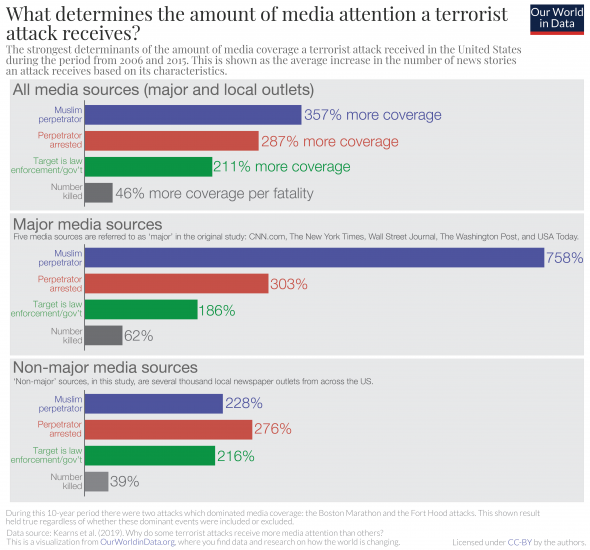

Why practise some terrorist attacks receive more than media attention than others?

Terrorism receives media attention which is disproportionate to its frequency and share of deaths. This is as well the intention of terrorists. Fright and attention is, later on all, a core tactic of terrorism: media covering the attack is a key office of the terrorist'south strategy.24 Terrorists are rarely successful at hijacking airplanes anymore. Simply they are very successful hijacking global news cycles.

Merely media coverage of terrorism is also highly diff: some events receive a lot of attention while well-nigh receive very little.25

Which are the characteristics that influence whether an attack is covered in the media or not? A previous study which looked at terrorist attacks in the U.s. from 1980 to 2001 establish they received more attention if there were fatalities; airlines were a target; it was a hijacking; or organized by a domestic group.26 Incidents received less coverage if they are framed equally a crime (akin to homicide rather than terrorism, for which there is non always a clear boundary).27

What does this relationship expect similar mail-9/11? In a recent written report, researchers looked at the differences in media coverage of terrorist events in the U.s.a. from 2005 to 2015.28 Kearns et al. (2019) focused on three fundamental characteristics: who the perpetrator was; the target of the assail; and the number of people killed. They assessed how these factors affected the amount of coverage attacks received in the US media.

We've summarized the results of their assay in this visualization. It'south presented in three panels: for all media outlets (top); for major national news sources only (middle); and 'non-major' sources (bottom). In this report the authors define 5 major news sources equally CNN.com, the New York Times, Wall Street Journal, the Washington Post and United states Today. 'Non-major' sources are thousands of local news outlets.

What'southward striking is the much larger coverage if the perpetrator was Muslim. Across all media sources, attacks received on average 357% greater coverage if the attacker was Muslim; for major outlets this was higher however at 758%. It appeared to play less of a role for local outlets. From this analysis nosotros besides see that media coverage was college when the perpetrator was arrested (partly because an arrest is a reportable event in itself); the target of the attack was police force enforcement or government; and when people were killed in the attack. 1 boosted fatality meant an average increase of coverage by 46%.

Which events practice and do not receive media coverage matter: evidence shows that media plays a defining role in shifting public opinion; perceptions of the importance of item issues; and national policy conversations.29 It tin can accept a meaning touch on on how the public perceives terrorism and its associations.

In item, increased coverage when a perpetrator is Muslim presents an unbalanced overview of The states terrorism to the public. In the dataset that this written report relied on, Muslims perpetrated 12.5% of attacks in the The states, still received half of the news coverage.

Combined with the fact that terrorism in general gets a asymmetric corporeality of media attention, the fact that the worst attacks – those that cause the greatest number of deaths – become most attending further exacerbates public fright. But it does mean that it'due south not just terrorism that receives a lot of attention; information technology's the rare only well-nigh extreme events that become easiest for united states to think.

One of the chief motivations for our work at Our Globe in Data is to provide a fact-based overview of the world we live in — a perspective that includes the persistent and long-term changes that run every bit a backdrop to our daily lives. We aim to provide the complement to the fast-paced reporting we see in the news. The media provides a near-instantaneous snapshot of single events; events that are, in most cases, negative. The persistent, large-calibration trends of progress never brand the headlines.

But is there prove that such a disconnect exists betwixt what nosotros meet in the news and what is reality for well-nigh of the states?

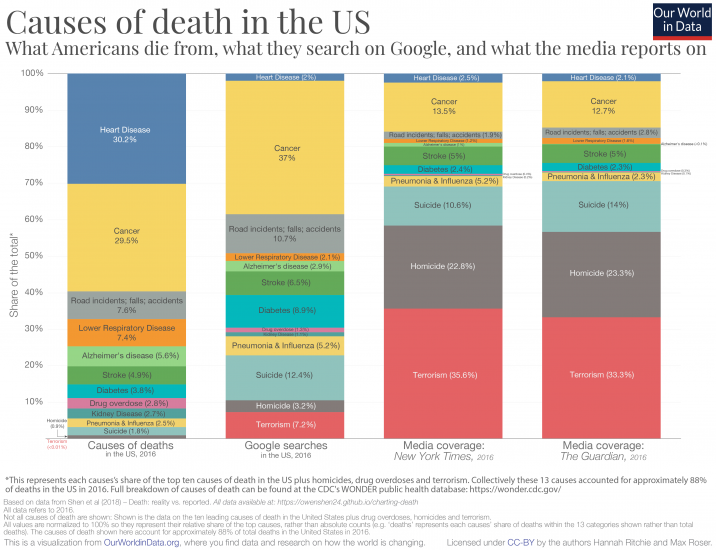

One written report attempted to look at this from the perspective of what we die from: is what nosotros actually dice from reflected in the media coverage these topics receive?xxx

To answer this, Shen and his team compared four key sources of data:

- the causes of deaths in the USA (statistics published past the CDC'south WONDER public health database)

- Google search trends for causes of deaths (sourced from Google Trends)

- mentions of causes of deaths in the New York Times (sourced from the NYT article database)

- mentions of causes of deaths in The Guardian paper (sourced from The Guardian article database)

For each source the authors calculated the relative share of deaths, share of Google searches, and share of media coverage. They restricted the considered causes to the peak ten causes of death in the The states and additionally included terrorism, homicide, and drug overdoses. This allows for united states to compare the relative representation beyond different sources.31

What nosotros dice from; what we Google; what nosotros read in the news

Then, what do the results look similar? In the chart hither I present the comparing.

The first column represents each cause's share of US deaths; the second the share of Google searches each receives; third, the relative article mentions in the New York Times; and finally article mentions inThe Guardian.

The coverage in both newspapers here is strikingly like. And the discrepancy between what we actually die from and what we get informed of in the media is what stands out:

- effectually one-third of the considered causes of deaths resulted from middle disease, yet this cause of death receives only ii-iii percent of Google searches and media coverage;

- but under one-third of the deaths came from cancer; nosotros actually Google cancer a lot (37 percent of searches) and it is a pop entry here on our site; merely information technology receives only 13-14 percent of media coverage;

- we searched for road incidents more frequently than their share of deaths; however, they receive much less attending in the news;

- when it comes to deaths from strokes, Google searches and media coverage are surprisingly balanced;

- the largest discrepancies concern violent forms of decease: suicide, homicide and terrorism. All 3 receive much more relative attention in Google searches and media coverage than their relative share of deaths. When it comes to the media coverage on causes of decease, violent deaths business relationship for more than two-thirds of coverage in the New York Times and The Guardian but account for less than iii percent of the total deaths in the Usa.

What's interesting is that what Americans search on Google is a much closer reflection of what kills the states than what is presented in the media. I way to think nigh it is that media outlets may produce content that they think readers are well-nigh interested in, but this is not necessarily reflected in our preferences when nosotros look for information ourselves.

[Clicking on the visualization will open it in college resolution; The nautical chart shows the summary for the year 2016, but interactive charts for all available years are available at the cease of this weblog.32 ]

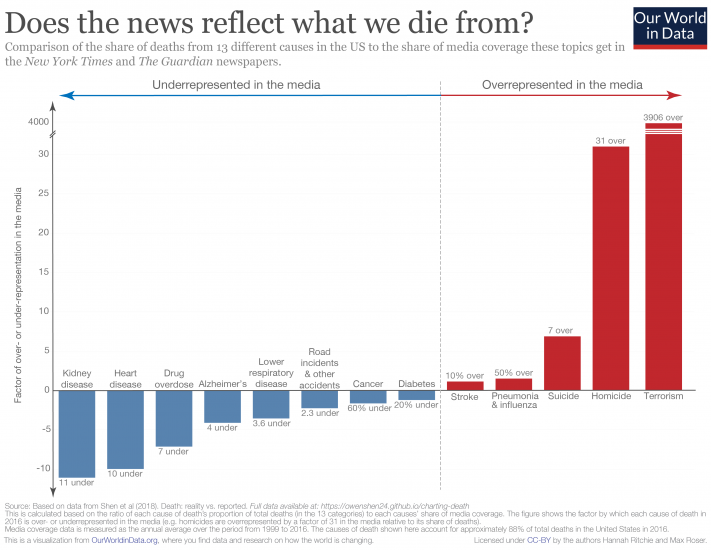

How over- or underrepresented are deaths in the media?

As we can see clearly from the chart above, at that place is a disconnect between what we die from, and how much coverage these causes make it the media. Another style to summarize this discrepancy is to calculate how over- or underrepresented each crusade is in the media. To do this, we simply summate the ratio between the share of deaths and share of media coverage for each cause.

In this nautical chart, we see how over- or underrepresented each cause is in paper coverage.33 Causes shown in red are overrepresented in the media; those in blue are underrepresented. Numbers denote the cistron by which they are misrepresented.

The major standout hither – I had to break the calibration on the y-axis since information technology's several orders of magnitude higher than everything else – is terrorism: it is overrepresented in the news past almost a factor of 4000.

Homicides are also very overrepresented in the news, by a cistron of 31. The most underrepresented in the media are kidney disease (11-fold), eye disease (ten-fold), and, possibly surprisingly, drug overdoses (7-fold). Stroke and diabetes are the ii causes well-nigh accurately represented.

[Clicking on the visualization will open it in college resolution].

Should media exposure reflect what we dice from?

From the comparisons above, information technology's articulate that the news doesn't reflect what we die from. But at that place is another important question:should these be representative?

There are several reasons we would, or should, await that what we read online, and what is covered in the media wouldn't correspond with what we really die from.

The showtime is that nosotros would look there to exist some preventative aspect to data nosotros access. In that location'south a strong statement that things we search for and gain data on encourages united states of america to have action which prevents a further death. There are several examples where I tin imagine this to be true. People who are concerned well-nigh cancer may search online for guidance on symptoms and be convinced to see their doctor. Some people with suicidal thoughts may seek aid and back up online which later results in an averted death from suicide. We'd therefore expect that both intended or unintended exposure to information on particular topics could prevent deaths from a given crusade. Some imbalance in the relative proportions therefore makes sense. But clearly there is some bias in our concerns: most people dice from heart disease (hence information technology should be something that concerns usa) nonetheless only a modest minority seek [mayhap preventative] information online.

2d, this study focused on what people in the The states dice from, not what people beyond the world dice from. Is media coverage more representative of global deaths? Not really. In another blog postal service, 'What does the earth die from?', I looked in particular at the ranking of causes of decease globally and by country. The relative ranking of deaths in the U.s. is reflective of the global average: most people die from heart affliction and cancers, and terrorism ranks last or second terminal (alongside natural disasters). Terrorism deemed for 0.06 per centum of global deaths in 2016. Whilst we'd look non-US events to feature in the New York Times,global news shouldn't substantially touch representative coverage of causes.

The third relates to the very nature of news: it focuses on events and stories. Whilst I am frequently critical of the messages and narratives portrayed in the media, I take some sympathy for what they choose to cover. Reporting has become increasingly fast-paced. Equally news consumers, our expectations have speedily shifted from daily, to hourly, down to minute-past-infinitesimal updates of what'south happening in the earth. Combine this with our attraction to stories and narratives. It's not surprising that the media focuses on reports of single (inadvertently negative) events: a murder case or a terrorist set on. The almost underrepresented cause of expiry in the media was kidney disease. But with an audience that expects a minute-by-minute feed of coverage, how much can possibly be said about kidney disease? Without conquering our compulsion for the latest unusual story, we cannot wait this representation to be perfectly balanced.

How to gainsay our bias for single events

Media and its consumers are stuck in a reinforcing cycle. The news reports on breaking events, which are often based effectually a compelling story. Consumers want to know what'southward going on in the world— we are quickly immersed past the latest headline. Nosotros come to expect news updates with increasing frequency, and media channels have clear incentives to deliver. This locks u.s. into a cycle of expectation and coverage with a strong bias for outlier events. Nearly of us are left with a skewed perception of the world; we think the earth is much worse than information technology is.34

The responsibleness in breaking this bike lies with both media producers and consumers. Will we always stop reporting and reading the latest news? Unlikely. But we can all exist more conscious of how nosotros let this news shape our agreement of the world.

And journalists can do much ameliorate in providing context of the broader trends: if reporting on a homicide, for example, include context of how homicide rates are irresolute over time.35

As media consumers we can be much more aware of the fact that relying on the 24/7 news coverage alone is wholly insufficient for understanding the state of the world. This requires us to check our (often unconscious) bias for unmarried narratives and seek out sources that provide a fact-based perspective on the globe.

This antitoxin to the news is what we try to provide at Our World in Information. It should be attainable for anybody, which is why our piece of work is completely open-admission. Whether you are a media producer or consumer, feel free to take and use annihilation you detect here.

Boosted information

What we can and can't know about terrorism from the Global Terrorism Database

Summary

In our enquiry on terrorism we rely on the Global Terrorism Database (GTD) as a key source of data on incidents and fatalities from terrorism across the world. It'south the most comprehensive database of incidents to engagement. It does, however, have limitations which we think should be clear before making inferences from trends or signals represented by the data.

In summary, this is our cess of what the GTD should and should not exist used for:

- Recent data – peculiarly over the by decade – is likely to be sufficiently complete to infer the distribution of incidents and fatalities across the world, and how they accept inverse in recent years;

- The consummate series, dating dorsum to 1970, for North America and Western Europe we wait to be sufficiently complete to infer trends and changes in terrorism over time;

- GTD data – as its authors acknowledge – undercounts events in the earlier period of the database – the 1970s and 1980s in detail. We would circumspection against trying to infer trends in terrorism globally since the 1970s;

- We would also circumspection against trying to infer trends in terrorism across most regions – with the exception of North America and Western Europe – in the earlier decades of this dataset.

In the surface area of terrorism research, at that place are now multiple databases bachelor which attempt to tape and detail terrorist incidents across the world. Some of the most well-known databases include International Terrorism: Attributes of Terrorist Events (ITERATE); RAND Database of Worldwide Terrorism Incidents (RDWTI) and the Global Terrorism Database (GTD). Nosotros accept a more detailed expect at the differences in estimates from these 3 databases hither.

In our research on terrorism we rely mostly on the Global Terrorism Database for multiple reasons: information technology's an open-access resource made available for researchers; it is the most up-to-date database available (RAND, in contrast, only extends to 2009); and is the most comprehensive in terms of the number of incidents covered.36

Since 2006 the database has been curated and maintained by the National Consortium for the Report of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (Offset), at the University of Maryland. In 2007 it was officially published equally an bookish output in the journal Terrorism and Political Violence, and since then has been one of the widely used resources within academic inquiry on terrorism.37 A big body of peer-reviewed literature on topics ranging from global or regional trends in terrorism; its link to poverty and socioeconomic factors; governance; and counter-terrorism strategy rely on information technology equally the most detailed catalogue of terrorist incidents.38 , 39 , 40 The GTD also forms the basis of the Global Terrorism Index published past the Institute for Economics & Peace (IEP).

The GTD is therefore well-respected and highly-regarded as a comprehensive data source on global terrorism. It does, notwithstanding, have limitations which nosotros think should be clear earlier making inferences from trends or signals represented by the data.

There are two main limitations or challenges with whatever long-term dataset on terrorism:

- The completeness of the database over time;

- how the concept of 'terrorism' is defined, which affects which incidents are or aren't included in the dataset.

Completeness of terrorist incidents over time

The GTD – as with other terrorism databases – are curated through records and assay of print and electronic media.41 This process has undoubtedly go easier over time. Nosotros wait that the collation of incidents beyond the world today and in the recent past is sufficiently consummate to understand the global distribution of terrorist incidents and how they take changed over time. A valuable resource which also provides impressive accounts of terrorist incidents across the earth is the many detailed entries in Wikipedia by year, by region or by country. Using this as a cross-reference with the GTD, we have high confidence in the completeness of global information in recent years.

Where we accept less conviction is the completeness of the information for inferring longer-term changes. The GTD extends dorsum to 1970. In their accounts of the GTD, the authors of the database acknowledge that data for this earlier catamenia most likely undercounts the number of terrorist incidents and victims.42 This is understandable: it seems unlikely that all terrorist incidents in the earth in the 1970s were (1) reported in print media; and (two) that all print reports beyond the world could exist traced, collected and analysed. The shift to digital media in recent years has made this procedure much easier.

Global records of terrorist incidents – at least in the beginning half of the dataset – are therefore probable to be an underestimate. We accept found no research which attempts to quantify the extent of this underestimate, so we cannot say past how much.

We do think some countries or regions – most notably the US and Western Europe – have a high caste of abyss over these decades. Since 1970, the GTD has been maintained by iv organizations, all of them US-based. Until 1997 the GTD was collated past Pinkerton Global Intelligence Service (PGIS) which trained U.s.a. researchers to place terrorist incidents from reports, governmental records and international media to appraise the risk of terrorism for clients. We would expect that this mandate would mean records are skewed towards more than consummate coverage of incidents in the US and countries with better reporting and records of incidents, such equally Western Europe.

In researching our posts: "Has terrorism increased in Western Europe?" and "Has terrorism increased in the United States?" we cross-referenced GTD records with the detailed accounts of these entries on Wikipedia.43 The GTD contains a much college number of incidents since those listed on Wikipedia for Europe are limited to attacks with ten or more civilians deaths. But for major incidents, there are closely matched.

For other regions we would caution confronting inferring trends over this complete time period. One central reason we take reservations about the completeness of before data is that there are several incidents nosotros would have expected to accept featured in the GTD which are not included.

Definition and methodology of assessing terrorist incidents

The other limitation to inferring particular trends in terrorism are changes in methodology and shifting – or unclear – definitions of terrorism over time. As we talk over in our mail 'What is terrorism?' there is no clear consensus on a definition of terrorism. Even within the research community there are differences in its scope, and there are often blurry lines between what constitutes terrorism as opposed to other forms of violence such as homicide and civil war.

We discuss the definition of terrorism used past the GTD here and how its methodology differs from other well-known databases hither. But an additional question when trying to understand changes, is whether the GTD had a consequent definition and methodology over time.

As previously mentioned, the GTD has been maintained past four organizations since 1970. With time – and particularly with the shift towards maintenance by an academic organization – the criteria for a terrorist incident improved and refined over time. Whilst researchers have attempted to retrospectively revise estimates (especially of the period from 1970 to 1997) based on updated criteria, the authors caution that there will inevitably be issues in information consistency over this period. This inconsistency will, most likely, exist expressed in an underestimate of terrorist incidents earlier in the dataset.

For this reason, again, we would be cautious about trying to infer changes in the prevalence of terrorism globally and across most regions since 1970.

How (and why) do estimates of deaths from terrorism vary?

In terrorism research, there are multiple databases available which attempt to record and particular terrorist incidents across the world. Some of the most well-known databases include International Terrorism: Attributes of Terrorist Events (ITERATE); RAND Database of Worldwide Terrorism Incidents (RAND/RDWTI) and the Global Terrorism Database (GTD).

In our inquiry on terrorism we present data from the Global Terrorism Database (GTD) for several reasons: it's the near comprehensive in terms of the number of incidents covered; it is the most up-to-engagement; and is open-access, and so widely used in academic research.44 RAND, for example, merely extends to the year 2009; and ITERATE is copyrighted, and not open-access for external users.

Nonetheless, estimates of the number of terrorist incidents and fatalities vary beyond these databases. Understanding why these differences exist is important for how this data is interpreted, and what we tin can conclude about the prevalence, causes and consequences of terrorism. Our understanding of the sources and frequency of terrorism can have a significant impact on many areas of guild and policy, including immigration, counterterrorism efforts, and international relations.

In the chart we see a comparison between estimates of terrorism fatalities from the GTD and RAND datasets. Both sources become back as far every bit 1970 (RAND to 1968), with GTD extending to 2022 whilst RAND was discontinued in 2009.

Here nosotros run across big differences between the sources until the tardily 1990s/Millennium, after which they appear to more closely converge. Why is this the example?

In a written report published in the Journal of Peace Research, Sandler (2014) looked at the differences in methodology, estimates, and conclusions from the various terrorism databases in item.45 Sandler found that the largest differentiator betwixt the databases was whether they recorded domestic, transnational, or both forms of terrorism. Domestic terrorist incidents are those where the venue, perpetrators and victims are all from the aforementioned country: for example, a terrorist attack committed in the U.s. past a United states citizen against victims from the U.s.a.. If an attack involves more than ane country – if the venue or victims of the assail are not the same land equally the perpetrators – then information technology is classified every bit transnational.

The largest difference betwixt the datasets is therefore that:

- GTD includes both domestic and transnational incidents across its entire dataset from 1970 onwards;

- RAND includes merely transnational incidents until 1997; thereafter it included both domestic and transnational;

- ITERATE includes simply transnational incidents.

If we expect again at the comparison of the GTD and RAND datasets in the chart beneath, this starts to make more sense. In the period prior to 1997, GTD consistently records more fatalities than RAND. During this time information technology included domestic incidents, whilst RAND did not. Since 1997 – when RAND likewise included domestic attacks – their figures accept converged.

A very clear example of this is seen if we expect at figures in the United kingdom. You tin can do this using the "Alter country" button in the bottom-left of the interactive nautical chart below. Here we see that during the 1970s and 1980s, RAND well-nigh no fatalities compared to the GTD. During the 1970s and 1980s, terrorism in the Uk – and Western Europe – was dominated by 'The Troubles' in Northern Ireland. Most deaths would have been classified as 'domestic terrorism', hence why they are included in the GTD but not the RAND figures.

Agreement the reasons for variations in the estimates of terrorist deaths may have a substantial impact on research and resource allocation. The root causes of transnational and domestic terrorism can be very different. The economic impacts – whether in the course of counterterrorism strategies; defense measures; or tourism impacts – tin also vary significantly.46 Understanding the prevalence and extent of both is therefore very important.

Across differences in the inclusion of domestic and transnational events, some differences in estimates be. Near databases used in terrorism research are curated and maintained from media reports, whether print or digital media. Differences in the completeness and choices of media sources can atomic number 82 to further variation betwixt databases. This is because media sources do not always report, or accurately report terrorist events; this can atomic number 82 to absent-minded or conflicting estimates.47

The GTD notes this limitation in its Data Collection Methodology. It states that "while the database developers attempt, to the best of their abilities, to corroborate each piece of data among multiple independent open sources, they make no further claims as to the veracity of this data", meaning that inconsistencies are entirely possible. Therefore, even when databases utilise the same definition of terrorism, the reported number of deaths depend on which media sources the database uses.

Definitions

Global Terrorism Database (GTD) definition

The information visualisations in this page are generated using the Global Terrorism Database (GTD), then it is important to sympathise the definition used in their construction. The GTD database uses the following definition of a terrorist set on:

The threatened or actual employ of illegal strength and violence by a non-land actor to achieve a political, economical, religious, or social goal through fear, coercion, or intimidation. In practice this means in order to consider an incident for inclusion in the GTD, all 3 of the following attributes must be present:

- The incident must be intentional – the outcome of a conscious calculation on the part of a perpetrator.

- The incident must entail some level of violence or firsthand threat of violence -including property violence, as well equally violence confronting people.

- The perpetrators of the incidents must be sub-national actors. The database does not include acts of state terrorism.

In add-on, at to the lowest degree ii of the following three criteria must be nowadays for an incident to be included in the GTD:

- Criterion 1: The deed must be aimed at attaining a political, economic, religious, or social goal. In terms of economic goals, the exclusive pursuit of profit does not satisfy this benchmark. It must involve the pursuit of more profound, systemic economic alter.

- Criterion 2: There must be evidence of an intention to coerce, intimidate, or convey some other bulletin to a larger audience (or audiences) than the immediate victims. It is the act taken as a totality that is considered, irrespective if every individual involved in carrying out the act was aware of this intention. As long as whatsoever of the planners or decision-makers behind the attack intended to coerce, intimidate or publicize, the intentionality criterion is met.

- Benchmark iii: The action must be exterior the context of legitimate warfare activities. That is, the act must exist outside the parameters permitted by international humanitarian police (peculiarly the prohibition confronting deliberately targeting civilians or non-combatants).

Bruce Hoffman definition

Their definition is closed tied to Bruce Hoffman'southward definition48:

We may therefore now effort to define terrorism as the deliberate creation and exploitation of fear through violence or the threat of violence in the pursuit of political change. All terrorist acts involve violence or the threat of violence. Terrorism is specifically designed to accept far-reaching psychological furnishings across the immediate victim(s) or object of the terrorist attack. It is meant to instill fright within, and thereby intimidate, a wider "target audience" that might include a rival ethnic or religious group,an entire land, a national government or political party, or public opinion in general. Terrorism is designed to create power where at that place is none or to consolidate power where at that place is very picayune. Through the publicity generated by their violence, terrorists seek to obtain the leverage, influence, and power they otherwise lack to issue political change on either a local or an international scale.

Legal definition

I important betoken of departure in many legal definitions of terrorism is computer hacking. The 'interference with or disruption to an electric organization' is explicitly stated in UK terrorism law; this does non fit into the definitions above which middle on violence. The UK the Terrorism Human activity 2000 defines terrorism as:

The apply or threat of action designed to influence the government or an international governmental organisation or to intimidate the public, or a section of the public; made for the purposes of advancing a political, religious, racial or ideological crusade; and it involves or causes:

- serious violence against a person;

- serious damage to a property;

- a threat to a person's life;

- a serious risk to the health and safety of the public; or

- serious interference with or disruption to an electronic organization.

Data Sources

Global Terrorism Database (GTD)

- Data: Terrorist attacks with 45-120 variables for each, including number of fatalities, injuries, weapons used, and perpetrators

- Geographical coverage: Global by land

- Time span: 1970-2016

- Available at: http://www.start.umd.edu/gtd/

RAND Database of Worldwide Terrorism Incidents

- Data: Date and location of the attack, weapons used, injuries, fatalities and description

- Geographical coverage: Global by land

- Fourth dimension span: 1968-2009

- Available at: http://world wide web.rand.org/nsrd/projects/terrorism-incidents.html

Integrated Network for Societal Conflict Inquiry (INSCR)

- Data: High casualty terrorist bombings

- Geographical coverage: Global by country

- Time span: 1989-2014

- Available at: http://world wide web.systemicpeace.org/inscrdata.html

International Terrorism: Attributes of Terrorist Events (ITERATE)

- Data: International terrorist incidents

- Geographical coverage: Global by country

- Time bridge: 1978-2011

- Available at: https://libcms.oit.duke.edu/data/sources/iterate, restricted to Knuckles University members

Source: https://ourworldindata.org/terrorism

0 Response to "Can I Wear the Global War on Terrorism Ribbon"

Post a Comment